This article appeared first in ICNC’s Minds of the Movement Blog.

A German radio station recently contacted me to ask why Hong Kong protesters have started using Pepe the Frog as a mascot for their pro-democracy protest. This question is intriguing considering that internet memes of Pepe are known in the West for their hatred and racist slurs, rather than freedom and democracy. In 2016, the Anti-Defamation League added Pepe to its database of hate symbols. Thus, many people find the recurrence of Pepe in the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong baffling, irritating, racist, or take it as evidence of “US intervention.”

Various media outlets have since featured the topic but without paying much attention to explanation. The New York Times, for instance, cites a protester saying, “Pepe did not carry the same toxic reputation in Hong Kong. Most of the protesters don’t know about the alt-right association.” A Business Insider article explains the adoption of Pepe as follows: “Simply put, Hongkongers thought it was just a funny face, and most didn’t know about its alt-right ties in the United States. In the eyes of Hongkongers, Pepe existed as a Hello Kitty character.”

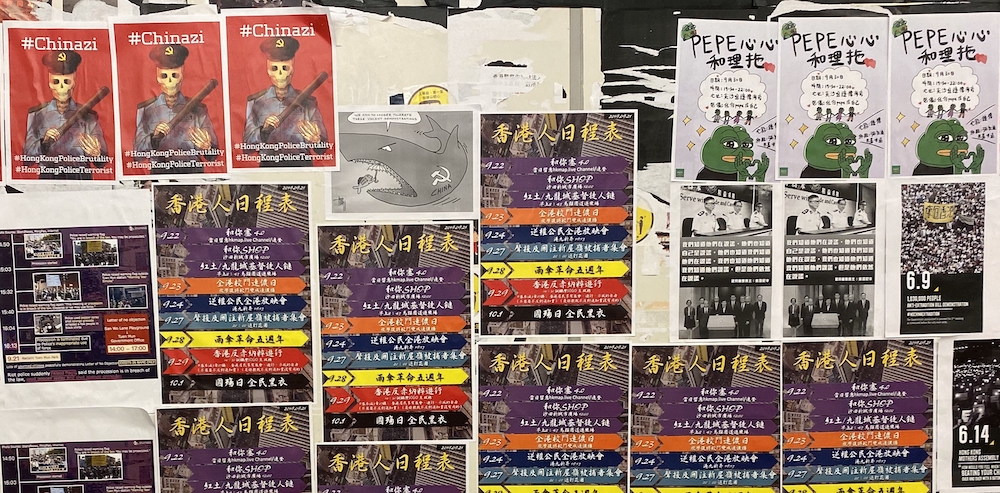

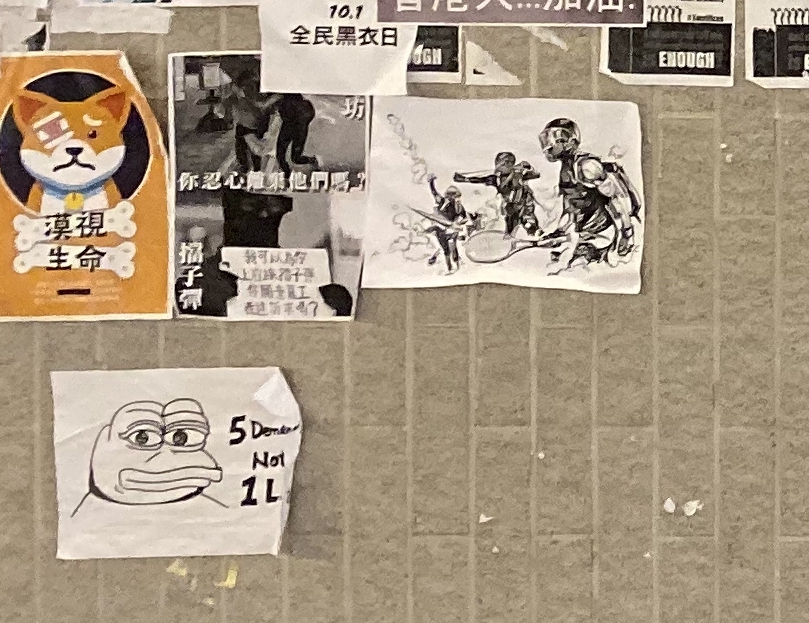

While these factors facilitated Pepe’s popularity, there is more to say about why and how Pepe has become such a widely used icon in Hong Kong today. The original version of Pepe, which looks frustrated or sad, is a relatable and disarming figure that resonates with how people feel about the situation in Hong Kong. Moreover, later into the movement, and somewhat contrary to what is being said in many mainstream media outlets, Hongkongers have consciously reclaimed Pepe from neo-Nazi groups to oppose what Hongkongers have called “ChinNazi.” In other words, it has been a strategic move rather than a random choice.

Icons, symbols, and mascots play important roles in protest movements. They help people identify with a movement, connect protesters with each other on a cultural dimension, and allow the creative (and often attention-grabbing) expression of dissent, e.g., in the form of protest art.

Yet many popular icons and internet themes have an ambivalent history. In this regard, the re-claiming of Pepe in Hong Kong can be a useful case study for other movements.

History of Pepe the Frog as an Internet Meme

Pepe the Frog originates from a 2005 comic by Matt Furie called “Boy’s Club,” in which Pepe and his friends smoke marijuana and watch TV all day. In 2008, internet culture picked up on Pepe, especially its sad and frustrated version. On sites such as 4chan, users posted thousands of Pepe memes, often drawn without sophistication in Microsoft Paint, just as Matt Furie did in the early 2000s.

In 2015, white supremacists started a campaign to take over Pepe as a hate symbol. In an interview with the HuffPost in 2016, Furie was puzzled by Pepe’s right swing on the Internet: “There is no hidden agenda,” said Furie. “There is no code with Pepe. Whatever he is, he is, for better or worse. […] I guess it’s just how the internet works.” But later, he let his own character die in a comic and, recently, took legal measures against the use of Pepe by racist groups. This year, the creator won a legal settlement with the far-right website “Infowars” to stop its use on websites and media he is opposed to.

Pepe is among the most successful internet memes of all time. Me.me, a search engine that crawls various social media sites to index memes, returns 40,080 memes for the search term “Pepe.” In comparison, for “grumpy cat,” another popular internet meme, the website has only 3,471 memes indexed.

So, why has Pepe become an icon for the Hong Kong protesters? In part, because in Asia, memes, comics, and anime characters enjoy a much wider presence in society than in the West.

Pepe as a Hong Kong Protester Mascot Used

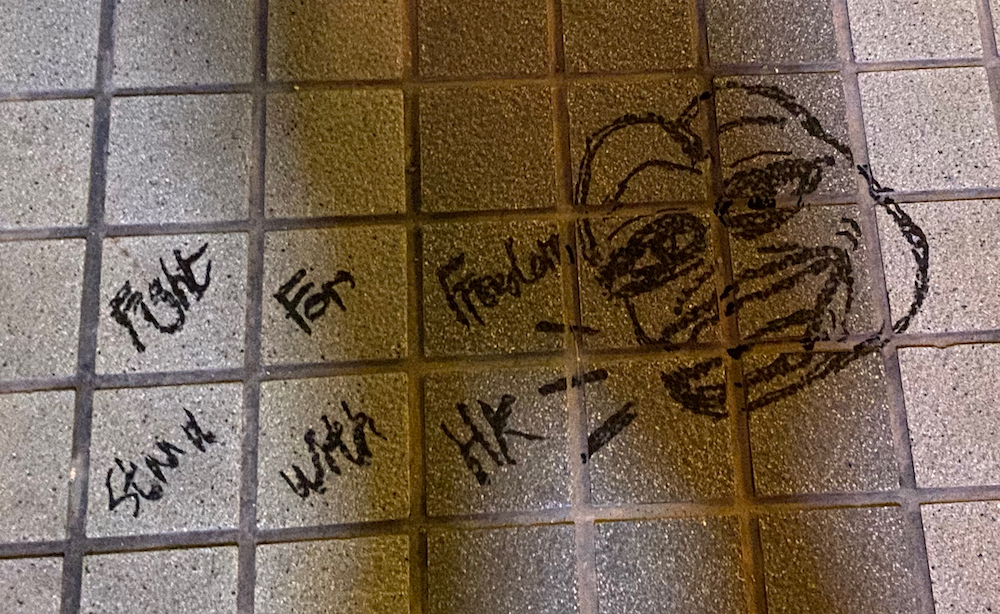

In June 2019, protesters started drawing Pepe figures on Lennon Walls (post-it walls expressing support for the movement in subways), holding protest signs featuring Pepe, and drawing Pepe on online calls for protest.

I observed first-hand Pepe, among other memes and comic figures, for the first time in June, and mainly among younger (and more often female) protesters. At the time, the frog was used in individual and creative forms of expression, such as on self-made protest posters, t-shirts, and so on, rather than by protest organizers themselves.

I think there are many reasons that Pepe has been popping up in protests more and more regularly since this past summer. First of all, Pepe is relatively easy to draw, and in most of his popular renderings, his look of disapproval is disarming, not hateful. Protesters relate to the frog memes, as they reflect many people’s feelings toward the situation in Hong Kong in a light-hearted way.

Second, as far as I can tell, there is no social norm in Hong Kong that would make it unacceptable to re-appropriate a symbol hijacked by fringe groups.

The Foreign Media Effect

Foreign media have been covering the apparent re-claiming of Pepe in Hong Kong since late August. The attention has made more protesters aware of Pepe’s use as a neo-Nazi symbol in the West. Some Hong Kong protesters, seeing the increase in global media attention in the West, have been incentivized to use the image to further increase media coverage. For instance, on September 30, a human chain across the Kowloon peninsula was themed after Pepe. This was the first time Pepe was used as an official protest theme, as opposed to individual expression.

Secondly, the same weekend, on October 1, the “March against Authoritarianism” attracted hundreds of thousands who used the newly emerged slogan “ChinNazi,” a term that associates the PR China with the Nazi regime, in their protest. What would be more powerful than re-claiming a neo-Nazi symbol to oppose “ChinNazi”?

Several other questions remain to be answered: Is framing the Hong Kong movement with a Western historical reference making it easier for Western audiences to understand why Hongkongers are protesting, and therefore making them more ready to sympathize? And perhaps most important at this critical moment in the city’s history, could bottom-up pressure on China from the people of Hong Kong be met with top-down pressure from the international community as a result?